![]()

Italy’s New Generation

A bright future in an ancient land, by James Suckling

Foradori, who has aspirations as a writer and musician, stepped into winemaking

at 19 to help her mother, who was managing the small family winery after the

tragic death of Elisabetta’s father years before. In the end, it was family

that brought them both into wine.

“They didn’t say that I had to do this,” says Foradori, who makes

stylish reds from a little-known grape called Teroldego in the shadows of the

Dolomite Mountains in Trentino. “I had a moral obligation. I was born in

the vineyards. I always remembered that.”

Shake hands with Elisabetta Foradori and you immediately know

that she is someone to be reckoned with.

This elegant woman has the grip of a champion arm wrestler – strength she

has acquired through years of working in her vineyards and making her wines.

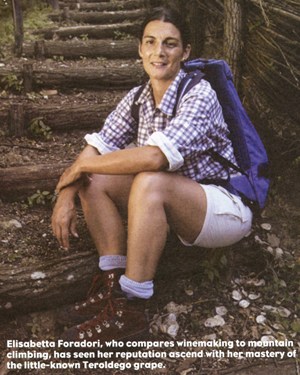

It hasn’t been easy for this single mother of four children – Emilio, 15; Theo, 13; Myrtha, 12; and Johannes, 7 months. Now 38, she has been running her winery, located in the valley of Trentino in the shadow of the Dolomite Mountains, for 20 years already, doing much of the vineyard and cellar work herself. It ratcheted up the degree of difficulty that she decided to make her name with a difficult and relatively unknown red wine grape called Teroldego.

“I love the history and the uniqueness of the grape,” she says, with a gleam in her brown eyes. “I am always trying to identify the best terroir and character for Teroldego.” Her top Teroldego, Granato, is a stunning red. It brims with exotic and ripe fruit character, yet remains polished and refined. The 1997 was classic in quality, a monument to the grape. But Foradori is still striving to improve. “I am sure there is even more to be done,” she says with conviction. She is an avid mountain climber and has scaled many of the highest peaks in her region. She applies the same sort of determination to her viticulture. “There is no secret. Great wines are born from great vineyards, and there is more and more to do here in my vineyards.”

The Foradori wine estate, about 26 miles south of Bolzano, is small and perfectly

kept. The winery looks like something out of an Alpine fable, with its chalet-style

wooden roofs and stone walls. The 12 acres of vineyards around the winery look

like a garden; everything is perfectly trained and managed. Foradori owns smaller

vineyards nearby, with the total equalling about 40 acres.

There are hundreds of acres of Teroldego grown in the area. Most of the fruit

ends up in the fermentation vats of nearby cooperatives, where grapegrowers

are paid primarily on quantity, not quality. These reds are fresh and fruity,

but nothing more. “You can’t make serious wine with 200 hectoliters

per hectare with 2,000 vines per hectare,” says Foradori. She usually harvests

about one-fourth that amount from vineyards with four times the number of vines

per hectare. Her frustration is evident.

“Most people have huge yields in the region, and no one is willing to change. It shows how generous Teroldego is that it can make decent wine with such high yields, but it is also depressing at times. I wish there were some like-minded people in the region. People who want to make excellent quality wines.”

Yet, nothing is going to stop Foradori. She has an enology degree from a local university, but it’s her drive and dedication that make the difference. “I owe it to the region, the grape and, more importantly, to my family,” she says. Foradori’s father died of cancer when she was a child, and as soon as she was old enough to seriously help her mother run their small winery, she was in the vineyards and cellars. “I have never questioned whether I should be making wine,” she adds.

Foradori is also working on a wine project in Tuscany. With a group of investors, she is developing a winery in the little-known but up-and-coming Maremma region there. Most of the new ventures in Maremma are near the coast, but hers is farther inland, near the town of Roccatederighi about 15 miles from Castiglione della Pescaia. The vineyards were planted a couple of years ago with Mediterranean varieties such as Cannonau (Grenache), Alicante and Carignano (Carignane). She admits that it is a gamble, considering the estate is at the outer limits of quality Tuscan wine production. But she loves the challenge.

“That’s why I like what I do,” she says. “It is doing everything

at the extreme limits. Making wine is like mountain climbing. It is very meditative.

You must be calm and patient and have luck. But you also have to improvise.

If something happens, you have to be able to react.”